Recently, I released Empty Black, my 2D shooter/puzzler/platformer. In this article, I’ll describe how I made the player movement deft and intuitive. Play the game before you read on, so you’ll know what I’m talking about.

My general approach was to change something, then try it out. I took the ideas for adjustments from several sources.

One. I examined the parameters affecting the movement of the player characters in other 2D platformers. Is the floor slippy? What is the ratio of sideways movement to jump height? Does the character accelerate as it moves? Is the character’s jump height affected by the length of time the player holds the jump button? Is the character slowed when it bumps into a moveable object?

Two. I examined the unusual behaviours of the player characters in other 2D platformers. Super Meat Boy makes the character leap away from the wall automatically when wall-jumping. Spelunky lets the character pull himself up and over ledges. In Castlevania, the character can do an extra jump while in mid-air.

Three. I got people to play test. Kemal told me that the character movement should be effortless. Specifically, if the character hits a wall near the top, it should slip up and over. Ricky told me it was weird that the player had no control over the height of the character’s jump. He showed me how, when hopping over an obstacle in a room with a low ceiling, he bumped his head. Ricky also pointed out the jarring effect of the initial slow down of the character when it lands after a jump. Everyone told me that airborne movement was too sensitive. Everyone told me that wall-jumping was too finicky.

Four. I read pieces written by programmers about their character movement algorithms. These pieces were mostly confined to short comments, rather than in-depth analyses. Hence, this article.

To the algorithm.

The short version: a pile of hacks.

The long version:

The player presses the jump key. The first question is: can the character jump? Which means: is the character in contact with anything that can be used as a place to jump from?

Empty Black uses Box2D to control the physics of the game world. Any movements are subject to Box2D’s models of the forces of friction and gravity. Further, Box2D handles the reactions of objects that collide: bounces, shoves, spins and slides. The game can interrogate Box2D and ask what objects a particular object is touching. If the character is currently touching something solid, the character may jump.

Except, it’s not quite that simple. As well as leaping from the ground, the character can wall-jump. This means landing and clinging onto a wall, then jumping again, away from the wall.

This technique is used frequently as a way for the player to get the character up a narrow shaft. They jump it back and forth between the vertical, parallel walls of the shaft, ascending with each jump.

This ability is bounded. The player may jump the character out from a wall and land it on the same wall. At this point, it may not jump again. If the player tries to make it jump, the character will fall. This bound is there to improve the gameplay. It is easier to design fun levels if I can rely on the unscalable nature of a solitary wall.

The bound makes it harder to decide if the character has a solid footing. The character should be able to jump from the ground as many times as the player likes. But it should not be able to jump from the same wall twice in a row.

Fortunately, Box2D has a metaphysical object that complements the corporeal walls, enemies and bullets: the sensor. This spiritual creature has no physical presence. It has a location in the world and it registers collisions. The programmer can interrogate it about such collisions, just as with physical objects.

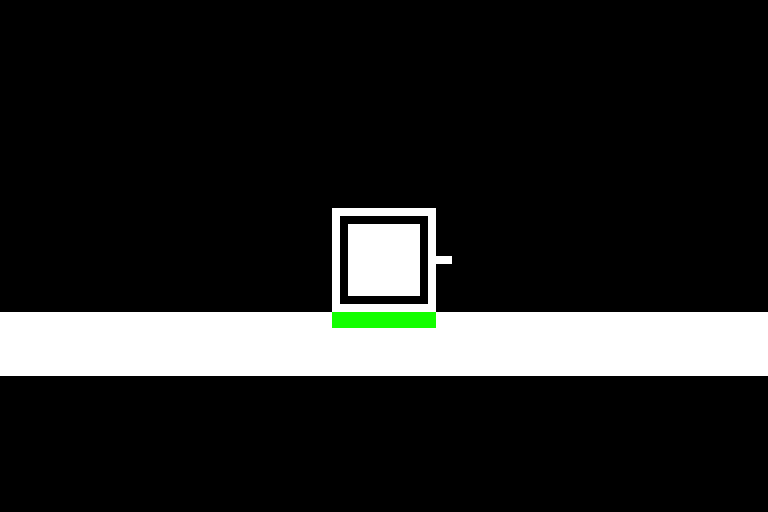

What I did was to attach a wide, short sensor to the bottom of the character. It would look like this, if you could see it:

Notice how the sensor overlaps the ground.

Now, instead of asking the character object about collisions, the game asks the character’s bottom sensor.

How does that help? It doesn’t. But I can attach two more sensors to the character, one on each of its sides.

This means that the game can ask each sensor if it is touching anything. If the bottom sensor is touching some solid footing, jumps are always allowed. If only a side sensor is touching a solid footing, the game must investigate further.

Jumps will be allowed in all cases but two.

One. The character lands against the wall it has just jumped from.

The game keeps a record of the last sensor that registered the solid footing for a jump. If it was a side sensor, and the character is using the same sensor for registration of the current solid footing, the jump is not allowed.

If the player loses control during a wall-jump ascent, the character will begin to fall. The player might manage to press jump as it hits a wall on its way down. It is possible that this wall will be the one they most recently jumped from. If it is, the jump would be prevented. However, there is an exception that permits the jump if the character is lower than it was when it jumped the time before. This exception allows the player to recover from their mistake. It makes the controls more forgiving.

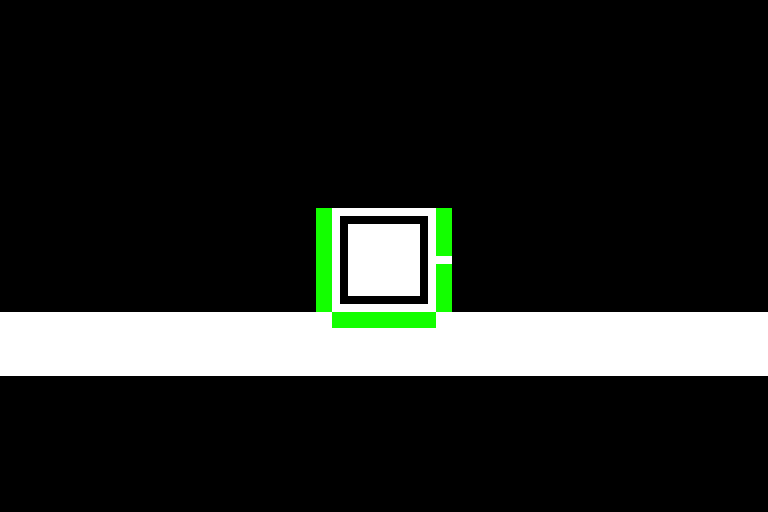

Two. The character lands and sticks to the wall. The player continues to press the direction key that holds the character against the wall. They press jump again. The jump is not allowed. If it were, the character would slide up the wall like this:

To stop this, the game only allows the jump if the player is not pressing the character into the wall.

There is an exception. If the character is near the top of a wall, it may jump. This lets it slip up and over the wall.

The game now knows if the character is allowed to jump. To enact the jump, upward force is applied for a single instant. The character’s velocity is high when it first starts moving. It is progressively attenuated by gravity. Some distance into the air, all the character’s momentum will be gone and it will begin falling.

If the player releases the jump button before the character has reached its peak in the jump, the character will immediately begin falling. I stole this idea from Super Meat Boy. The effect is that of a glass ceiling being inserted above the character’s head. This allows the player to control the height of the jump. It stops Ricky getting a sore head.

The magnitude of the force of the jump is usually constant. However, it is increased in two situations.

First, when the character is carrying a crate. This stops the weighted character’s jumps turning into lame little bunny hops.

Second, when the character is falling faster than usual. Imagine the character is wall-jumping and, because of a player fumble, it hits the next wall at a point lower than the point it jumped from. To help the player recover, their next attempt at a jump from a wall will lift the character with a force greater than normal. The difference from the normal force is proportional to the disparity between the normal and actual force of falling.

Now: sideways movement.

The player presses the left arrow key. What happens?

A leftward force is continually applied until the player releases the key. The magnitude of the force depends on how fast the character is currently moving. If it is at top speed, no force is applied. If it is stationary, a large force is applied. The idea is to get the character to top speed as fast as possible, then hold it at that speed. This makes the movement more predictable. It also solves Ricky’s second problem. The character immediately regains top speed after it lands a jump.

The player releases the key that moves the character left. What happens?

The character immediately stops. There is no slippiness. Thus, the character is easier to control.

When I was designing the character movement, it was hard to keep the code tidy. I tried to find the smallest number of rules that required the least subsequent modification with hacks.

Two examples.

One. I tried to eliminate the slippiness of the floor by setting the friction very high. But this had many undesired consequences. It was hard to get the player moving sideways at top speed without also making airborne movement too sensitive. Crates could no longer be shoved, and mis-throws would leave them perched on ledges. I added code to immediately stop the character upon release of the move key.

Two. Slipping up and over a ledge was just a matter of the player pressing the jump key near the top of a wall. But if the character was only half way up a wall, such a jump would mean it slid upwards and got stranded. I could have left that behaviour as it was. But that would have made wall-jumping harder. I could have automatically jumped the character away from the wall. But that seemed too nannyish. So, I prevented jumps when the player was pressing into the wall but was not near the top of it.

In both cases, it was worth slightly modifying a generally correct behaviour with an ugly but small hack that had no repercussions.

The general approach was to try stuff to explore the options. But the goal was a few broad rules. I did this by only deciding on a permanent change after a careful check of the ramifications. And I sometimes entirely remade the rules, as with the addition of the sensors to the character.

Here is a pocket-sized summary for you.

Examine the overall behaviours and specific parameters of other games. Get as much player feedback as you can. Make many changes. Tidy up after yourself.

Comments